News, Issue 18/2024

Global water crisis – rivers around the world are drying up

It has never been this dry – according to the latest report, State of Global Water Resources 2023, published on October 7 by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The global water resource crisis is a fact confirmed by hydrological data, including exceptionally low river flows. In many parts of the world, water shortages are beginning to affect local communities, agriculture, and ecosystems.

Low river flows – from the Amazon to the Mekong

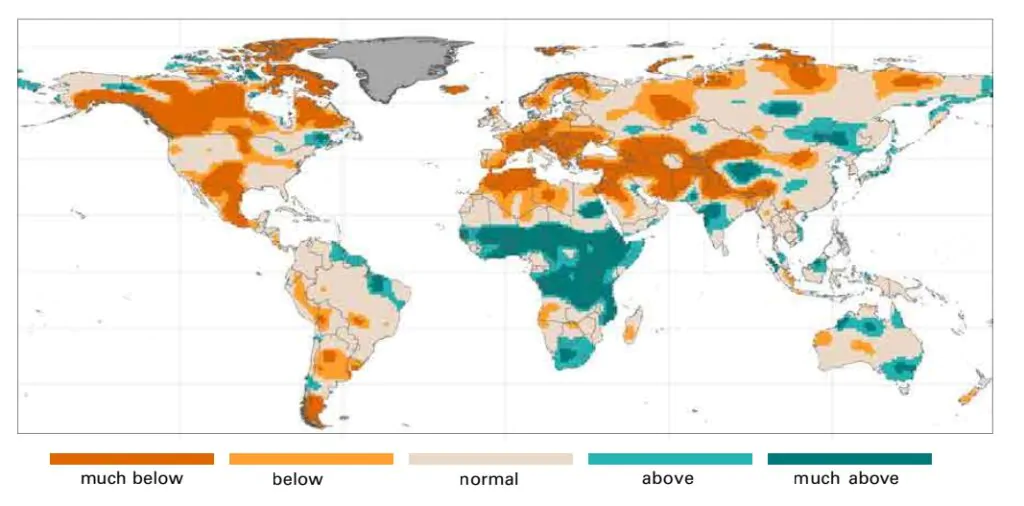

In 2023, as in the previous two years, more than 50% of major river basins saw below-normal river flows. Severe droughts affected the Americas, with water levels in the Amazon and Mississippi river basins reaching historic lows. In contrast, in the Horn of Africa, where the rainy season failed to bring expected rainfall for five consecutive seasons, 2023 was marked by catastrophic floods that claimed hundreds of lives – scientists attribute this to the influence of El Niño. Despite this, below-normal flows were recorded in the Nile, Congo, and Niger basins.

Low river flows were also noted in the largest Asian river basins – the Ganges, Mekong, and Brahmaputra, as well as across Central Asia and the Middle East. In contrast, there was significantly more water in the rivers of northern and central Europe, including the Danube and Dnieper. This data aligns with warnings about erratic weather patterns resulting from climate change.

Deficits in water reservoirs

The record-low river flows in the Americas, Asia, and parts of Australia also led to lower water levels in most reservoirs. Below-average inflows were recorded, particularly in India, New Zealand’s South Island, and the Murray-Darling Basin in Australia. Water shortages in reservoirs were also evident in the Mackenzie River basin in the USA, across Mexico, and in the Paraná basin. A similar situation occurred in the Middle East and Central Asia.

Paradoxically, water levels in many natural lakes remained within the normal range or even exceeded it – from Lake Superior in the USA to Lake Balaton and Tonle Sap in Cambodia. However, a particularly dramatic situation was noted at Lake Coari in the Amazon basin, where a heatwave and reduced inflows caused the water temperature to rise to 34°C. The warming resulted in the death of a significant number of Amazon river dolphins, the world’s largest freshwater dolphins.

Declining groundwater levels and glacier melting

Low river flows in many regions are not the only symptom of the hydrological crisis. In North America and Europe, groundwater levels in 2023 were significantly below normal – hydrological drought also affected Poland. A similar problem was observed in Chile and Jordan, but according to WMO experts, it is more the result of excessive water extraction than climatic factors. Additionally, lower-than-average soil moisture was recorded across the Americas, North Africa, and the Middle East, especially from June to August. Winter in the Northern Hemisphere brought significantly less snow than usual (except in the northern United States).

During 2023, the world’s glaciers lost over 600 gigatons of water – the most in five decades. Losses were observed in all glaciated regions of the world. Overall, total terrestrial water resources, including rivers, lakes, groundwater, soil moisture, snow cover, and glaciers, were clearly below average on most continents last year. Notable exceptions were recorded in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Tibetan Plateau, and some regions of India, Australia, and northern South America.

source: State of Global Water Resources report 2023 WMO-No. 1362