Issue 3/2024, Issue topic

Piotr Bednarek on the challenges facing Polish water management

This article needs a few words of introduction, as its publication was not so obvious. A few weeks ago, a video by Piotr Bednarek about the challenges facing Poland’s water management surfaced on social media. I listened attentively to the words of a person who is close to the problems concerning the management and operation of Polish rivers, that is, he works in the field. In recent weeks we have devoted considerable space in Water Matters to topics related to the future of water management in Poland, but these were not the views of NGOs. Piotr Bednarek of the Free Rivers organization is a man of action and has little time to write, so – at my urging – he has agreed to publish his social media statement in the form of the following text. Agnieszka Hobot – editor-in-chief.

Challenge one – fighting drought

All three challenges are partly the result of human actions, including climate change, which intensifies these challenges. So let me start with the drought. The Polish Economic Institute, an organization with ties to the government for decades, has calculated that crop losses associated with droughts amount to more than PLN 6 billion a year in Poland. Why is this happening? It would seem that the cause is too little rainfall, right? Not necessarily.

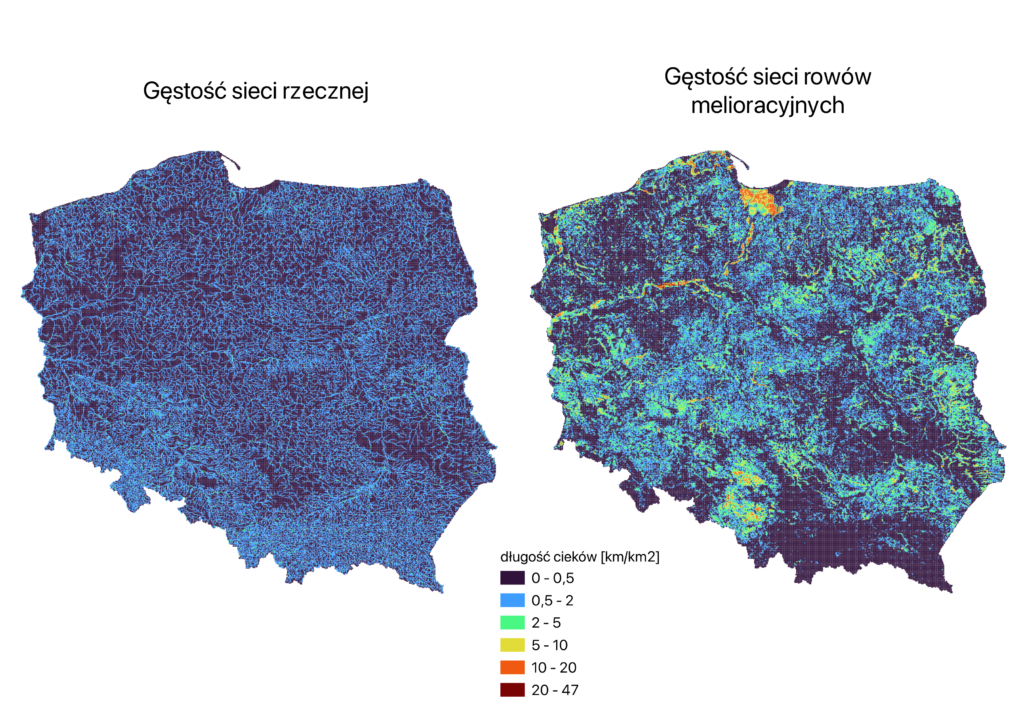

As temperatures rise, the amount of evapotranspiration increases – water evaporates faster when it is warmer. It rains about the same amount as in the past, only it is more unevenly distributed throughout the year. We have longer periods without rain and short periods with very heavy rain. But that’s not all. Take a look at these two maps I’ve developed to illustrate what we do with the water that falls on our country’s land.

On the map to the left, we see the density of the river network in 1 x 1 km squares, so with an area of 1 km2. On the map to the right, in the same squares, we see the density of the drainage ditch network. Their length in meters per square kilometer, as you can see in the legend, is many times greater than the length of natural watercourses. This means that we have accelerated water runoff from huge areas to a very large extent. We have 2-3 times more ditches in Poland than rivers (available databases such as BDOT10k are incomplete) in terms of length. They are most densely located in the proglacial valleys, where peat bogs previously existed, such as in the valley of the Notec River.

This map also shows that the density of natural watercourses is higher in the Carpathians than ditches. There are practically no drainage networks there, but their functions are performed by skid roads, of which there are tens of thousands of kilometers in the eastern part of these mountains.

So we accelerate water runoff on a massive scale, and then we are surprised that we have a drought. The idea of solving this problem by baffling rivers or building dams and reservoirs is pure demagoguery. Look at how few rivers we have at our disposal, and how much opportunity the ditches offer. I’m not suggesting that they should all be backfilled or that levees should be built on them all. Some are undoubtedly needed: those that drain residential areas or farmland. But ditches in swamps, forests, national parks or reserves require immediate, not just decisions, but even action.

In forests and natural vegetation alone, we have more than 70,000 in Poland. km of ditches. This is a huge field for action and improvement. Poland is being drained on a very broad spatial scale. If we continue to drain water very quickly into rivers, and then try to catch some of it in retention reservoirs, we would then have to somehow redistribute it, i.e. pump it uphill. This is an action that is completely meaningless. There are no systems in place in Poland to put water from reservoirs, such as the one in the country, back into farm fields. Włocławek or Jeziorsko, and farmers have to fend for themselves. An example of this is Patryk Kokocinski from Wielkopolska, who creates dams on ditches on his own initiative.

Extinction of life in rivers

The second challenge, in my opinion as important as the drought and related to it, is to prevent the extinction of life in our rivers. The shortage of water causes some of them, especially the smallest and in the upper reaches, to dry up completely. The return of life to these watercourses is not obvious, and with climate change it will be even more difficult, as the drying up process will intensify. If we don’t restore retention, some of the rivers will disappear within our lifetimes. But drought is not everything.

One of the main factors causing life in rivers to die out is the fragmentation of their course by dams, reservoirs, weirs, thresholds, water stages, stone ramps. Fish and other organisms are unable to migrate, to move up and down the river. And these migrations are essential to life for most species: to spawn in some convenient place, get food or escape drought or pollution.

Without restoring the longitudinal continuity of the watercourses, there is no way we can have rivers full of life. Last year’s Oder disaster showed the extinction of fish in the great river on a massive scale. The situation has been caused primarily by pollution that flows in large quantities from mines and industrial plants, but also from treatment plants that do not function properly or illegal discharges. Our rivers are also severely zeutrophied by nutrient runoff from fields. This is one of the main reasons that they do not function naturally.

In addition to pollution, we also have effects that we won’t see so easily. Because whether or not there are fish in the river is not visible to the naked eye. It is necessary to conduct specialized research. The river will look the same with and without fish. Based on years of monitoring, we know how disastrous the state of life in rivers is both in Poland and across the continent.

In Europe, fish populations of dozens of migratory species have declined by more than 90 percent. only in half a century. This is a drastically rapid change and the odds are against many species becoming extinct forever. The same is true for mussels, which have it even worse, as they are more sensitive to pollution and regulation of watercourses. We need to change our approach to rivers. Start dismantling unnecessary baffles, stop digging up troughs, which is also related to drought and flood prevention.

We need to stop doing maintenance work on thousands of kilometers of rivers. Of course, they are needed in conflict areas, but there are not as many such points as we think. Most of the interventions involve digging up the river with backhoes, mowing vegetation in it or pulling dead wood out of the riverbeds, and are carried out pointlessly. We are losing out financially and destroying biodiversity.

How to deal with flooding?

I have already moved on to the third of the challenges facing Polish water management, namely floods, especially flash floods. I recently read a paper predicting that, with high probability, the frequency of stationary storm cells will increase dozens of times over the next 80 years. Thunderstorms generating record high precipitation will definitely become more frequent as the climate continues to warm. The question is how we want to respond to it. Because we can ignore this and continue to raise the embankments and regulate the rivers. But it won’t work. We need to slow down runoff wherever possible, move the embankments away from the riverbeds, but above all, we need to take care of retention on a large spatial scale. Here the recovery of retention in ditches, which so far only accelerate runoff, can come to the rescue.

Another problem is conflict areas, where, for example, beavers flood the area or water overflows during floods, and then the most common answer is to regulate the river and deepen it. We need to change this paradigm. We need to slow down the flow and give the rivers their rightful areas. This will be profitable in the long run both for us and for biodiversity. Higher and higher embankments have the potential to become a huge danger, as do aging dams

There is another paradigm that applies to all three problems mentioned above, which we need to change. As I talk to land reclamationists, to people who do various maintenance work on rivers or ditches, I hear that there are fewer and fewer people willing to do such tasks, especially by hand. And since people don’t want to work that way, contractors hire heavy equipment that rips up the trough in a much bigger way. They do this despite being aware of the negative consequences of such actions. And this is where I miss such a click.

Since there are no people willing to be in the field all the time to supervise the water and infrastructure, to take appropriate action – to open or close, to adjust the height of the shanders in the levees – it is necessary to create a system in which less will depend on human activity. A system that will be less prone to making mistakes.

If you have watched the series “Great Water” about the Oder River flood, in which it was – perhaps in an exaggerated way – shown how human errors lead to serious events, you can realize that if we want to control what happens to water on a large scale, this control must be carried out continuously and very meticulously. And this is a problem, especially if there is a shortage of people willing to do such work. Solutions close to nature, giving back space to rivers, restoring natural retention may be the answer here.

A cost-effective answer in the long term. Perhaps hard to implement at first, since every politician prefers to be photographed at a newly commissioned large concrete dam than at a few wooden levees on a ditch. And this is understandable: big investments, big money, commitment to society. From a politician’s point of view, this is good for his support, but from the point of view of a hydrologist who knows how water functions in the landscape, it makes no sense.

And here I return to the maps with the density of the drainage ditch network and the river network. To sum up what I have said many times, we must try to give back to certain places to nature. Start with those in reserves already in place, in national parks, in wetlands, but also in forests whose water-protective functions need a definite rethink, especially in the Carpathians and Sudetes. We need to start managing water in a distributed rather than centralized way. I hope that the new government will be willing to use the expertise of experts who will be able to stop pointless yet costly investments. Do I believe it? Not quite, but still hopeful.

Piotr Bednarek – chairman of the board of the Podkarpackie Society of Naturalists “Free Rivers”; hydrologist, naturalist; doctoral student at the Department of Hydrology of the Institute of Geography and Spatial Management at Jagiellonian University; photographer; passionate about wild rivers and marshes.

Polski

Polski