W 20. anniversary of Poland’s accession to the European Union, the Foundation for the Development of Polish Agriculture (FDPA) has prepared a report that summarizes two decades of change in our agricultural sector. Polish Village 2024 is a publication focusing on the impact of EU funding on the functioning of farms and the lives of the rural population. It also contains valuable information on the environmental and climatic conditions of agricultural production.

Who lives in the countryside? Demographic changes

The FDPA report shows that over the past two decades, the population in Polish villages has officially increased by 2.5 percent. This phenomenon is partly due to the influx of urban residents interested in a better quality of life, but does not fully address the dimension of migration. Many farmers have gone abroad in search of work without checking out of the country. Demographic data show that inone-third of rural municipalities the population is increasing, in two-thirds it is decreasing – regional differences are also marked in many other aspects.

The Polish countryside is continually aging – in 2022. 19.8 percent of the population was in the post-working age. By comparison, in 2004, the rate was 15.5 percent. At the same time, the number of people in the pre-working age (0-17 years) is decreasing alarmingly. This trend is also observed in other European countries. The level of employment in the countryside has increased by 3 percent over the past two decades, but it is still much lower than in cities, at just 59.4 percent. Rural residents, however, earn up to 3.5 times more than when they joined the EU. The structure of their income has also improved, with more coming from gainful employment and less from social benefits.

Is Polish agriculture on the right track?

According to the report’s authors, Poland has made very good use of the opportunities associated with its accession to the EU. The European Single Market has allowed farmers to increase production and exports. Intensive investment has also helped, with 45 percent of the total. were financed with EU funds.

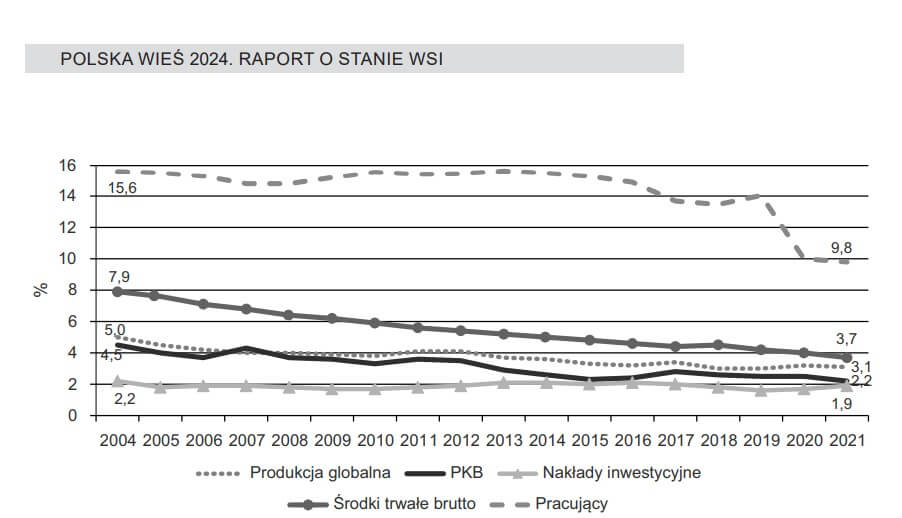

The decline in agriculture’s share of GDP from 4.5 percent is cited as positive. in 2004. to 2.2 percent. currently. The level of employment in the sector is also decreasing (from 15.6 percent of the total workforce to 9.8 percent), but this is still more than three times higher than in other European countries. Reservations can be raised about low productivity and insufficient farm size – the average in 2020. amounted to only 11.3 hectares. By comparison, German ones are up to six times larger. However, the number of farms in Poland continues to decrease, and the farms being liquidated are mainly the small ones, ranging from 2 to 20 hectares. Large and very large account for only 3.2 percent. of all units, but produce as much as 47 percent. total production.

If we take into account all agricultural production in the EU-27, Poland’s contribution is only 6.6 percent, although labor input is at 17.6 percent and land resources at 9.5. According to the report’s authors, this is evidence of the huge but still underutilized potential of the Polish countryside.

Agriculture and soil and water quality

From the point of view of Water Matters, a very important part of the report Poland’s countryside 2024 is the chapter on environmental and climate issues. On the one hand, agriculture is actively influencing the state of the natural environment, while on the other, it is facing the problems of climate change and a potential food crisis. Maximizing economic benefits is an approach that is no longer sufficient in thinking about the future of the Polish countryside. All the more so since the EU’s development is planned on the basis of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals – based on them, among other things. Green Deal policy and the Common Agricultural Policy.

Over the analyzed period of the last two decades, Poland’s agricultural land has decreased by 1.4 million hectares – arable land that was converted for construction and transportation development has disappeared. According to the report’s authors, the fact that areas with the most valuable soils account for a very high proportion of land allocated for non-agricultural purposes should be considered a worrying phenomenon. This demonstrates the inadequate legal protection of land that is most important for retention and biodiversity conservation.

More than half of the farmland is acidified, largely due to the amount of nitrogen fertilizer used, which has been steadily increasing since joining the European Union. Fortunately, as of 2015. The use of calcium fertilizers has also begun to increase, giving hope that the condition of the soils will improve.

In the context of water management, the report’s authors highlight the persistently inadequate capacity of retention reservoirs, which is only 6 percent. annual water runoff. Significant exceedances of the standards of eutrophication indicators in the studied surface water bodies (water bodies) are also a significant problem. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus in water is also the result of excessive fertilizer use in agriculture, which Directive 91/676/EEC combats. The authors of the report remind that the entire area of the country already has the status of an area particularly vulnerable to nitrogen pollution (OSN), which should entail the implementation of good practices for reducing fertilizer application rates and timing, as well as storage of natural fertilizers.

Instead, changes in the share of the population served by municipal wastewater treatment plants are indicated as very favorable. In the Polish countryside, the proportion rose from 18 percent. two decades ago to 46 percent. currently.

Polish countryside in the era of climate change

The FDPA report did not lack reference to the global warming of the atmosphere, which is shaping new conditions for agricultural production. In Poland, the last 20 years have seen a temperature increase of 0.29°C per 10 years, which means that in 100 years it could be as much as 3°C warmer. The slight increase in precipitation does not compensate for field evaporation resulting from warming. As a result, the Polish countryside is increasingly suffering from deep agricultural droughts of increasing scope.

Unfortunately, improvements in the sphere of technology and management introduced in recent years have focused mainly on increasing productivity and efficiency, leaving aside the issue of adapting operations to changing climate conditions. However, the Polish National Environmental Policy provides for such initiatives as the protection and development of mid-field and roadside tree plantings and the prevention of the exclusion of soils from food production. Positive changes in the Polish countryside are expected to be helped by ecoschemes implemented from 2023.

Rural entrepreneurship

Between 2004 and 2023, the Polish countryside received significant EU financial support for business development. The result was not only the aforementioned increase in farmers’ incomes, but also the modernization of the entire sector, including agri-food processing, improvement of the quality of human capital and the living conditions and aesthetics of rural areas. Funds obtained under SAPARD (Special Pre-Accession Program for Agriculture and Rural Development) and subsequent RDPs (Rural Development Programs) have helped create thousands of new jobs and new sources of income on farms, and have helped improve the tourist qualities of the Polish countryside.

At the same time, more than 65,000 rural small businesses were realized in direct support from 2002-2022. projects with a total funding of PLN 133 billion. According to the report’s authors, it is small business that should be a priority in rural development planning. In the west of the country, where the inflow of foreign investment and support for the non-agricultural sphere of the economy was greater, a much higher degree of deagrarianization was achieved, resulting in a better area structure of farms.

Ministerial criticism of the report Poland’s countryside 2024

During a meeting presenting the FDPA report, Agriculture and Rural Development Minister Czeslaw Siekierski pointed out the publication’s shortcomings, asking that it be supplemented in future editions. According to the head of the ministry, the summary lacked information on education and the level of education of rural residents, as well as the widening social disparity. There were also concerns about inconsistencies in data from the CSO.

At the same time, Minister Siekierski stressed the need to accelerate further changes. The Polish countryside will have to meet the challenges of the Common Agricultural Policy in the coming years, as well as the prospect of Ukraine’s accession to the EU. The minister also pointed to the development of new financial and market support instruments for farmers as key, primarily with a gradual shift away from direct payments.

Polski

Polski